“I’m definitely not an architect,” Daniel Arsham tells me when I ask him if he considers himself an artist or an architect. His body of work would allow him to aptly fall under a number of categories in the creative world from painting and sculpture to installation, architecture and stage design. He’s been commissioned as an artist and architect by some of the biggest names in design, yet if you ask him, he prefers to liken his work to an archaeological study rather than an art.

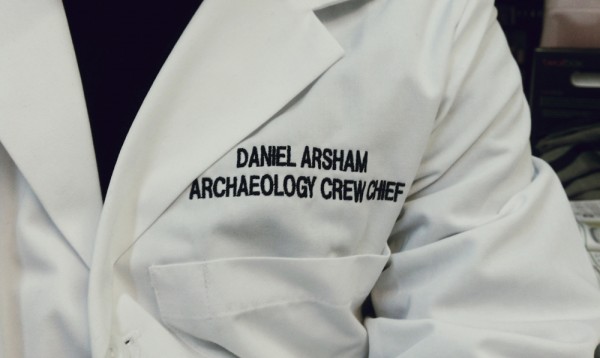

“I’m thinking about all these pieces as if you were talking to an archaeologist in the future,” Arsham elaborates as he holds a replica handgun he has casted in sand. Arsham is wearing a stark white lab coat that reads “Archaeological Crew Chief” as he gives me a tour of his Greenpoint studio on a rainy January morning. In a way, his workshop is an archaeological dig in and of itself, with remnants of past projects and in-progress works scattered throughout the space.

T

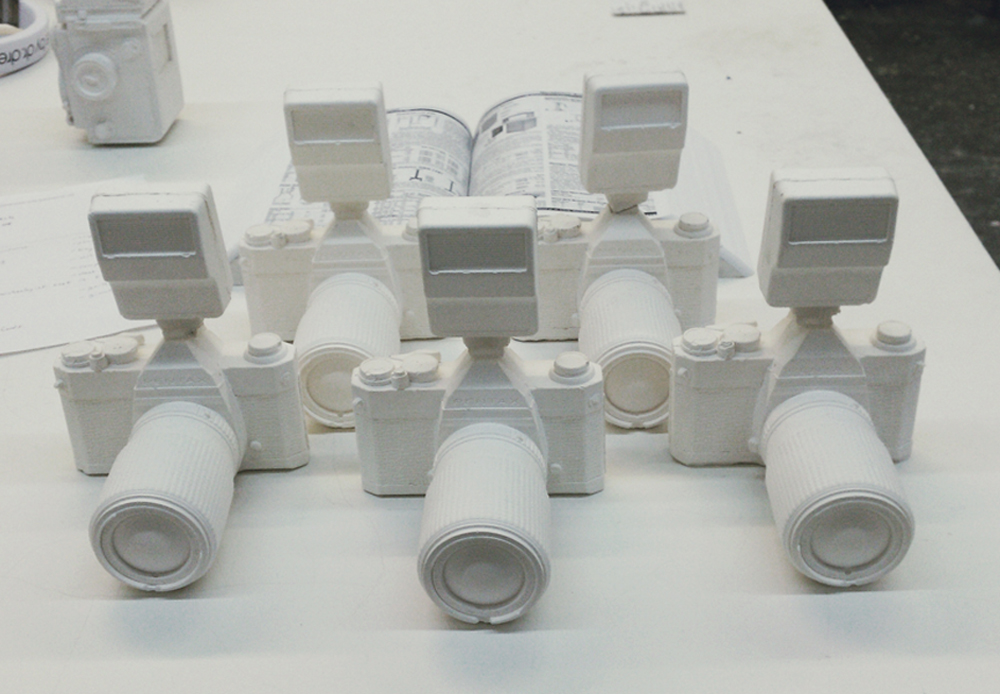

he aforementioned handgun is one of five replicas, as are the phones, clocks, and cameras that Arsham has casted in sand or plaster. “Objects of communication, objects of documentation, objects of quantifying time, and objects of control…” Arsham verbalizes their domains as he looks down at the evenly spaced objects on a white table in the center of his studio.

The 32-year old artist explains the pieces will eventually become part of a much larger body of work, though he has yet to discover exactly where it will go. “As in much of my other work, it’s about taking these objects out of context. By changing their form and their material, this is now a relic. It’s shaped like the original form but it looks almost like something you would find in an archaeological dig.” Arsham plans to present the objects upside down, sideways and otherwise astray from a normal approach. To him, they are future remnants, to be experienced as if the finder was not aware of their purpose.

T

he future artifacts display a “broken, eroded quality” to them, suggesting they have already weathered the passing of time. In fact, the white plaster cameras have already weathered multiple live performances at Arsham’s current exhibit Reach Ruin at the Fabric Workshop Museum in Philadelphia. “The choreographer that I work with very frequently Jonah Bokaer, created a work with me where the dancers are actually using these cameras like giant pieces of chalk, and they’re drawing with them on the floor, so the camera is digging into the floor, and begins eroding and breaking.”

Circles of chalk become the remnants of this performance, which are left for future visitors to encounter. The visitor then becomes aware that something has happened in this space, a realization that is enhanced with a video of the bygone performance projected on a wall in the exhibit, “almost as if the wall was a mirror looking back at the performance that’s no longer occurring.”

Eager to point out the influence of choreographer Merce Cunningham on this particular exhibit, Arsham recalled Cunningham’s inquisition to design a stage for him eight years ago: “I was 24 years old and this legend of modern dance says to me: “I’d like you to do this work for me. The piece is going to be forty minutes long. We’re going premiere it in a year and a half. See you at the premiere.” Cunningham worked in a way that allowed his influence and feelings to be “dissipated by this notion of chance,” and thus he did not work with Arsham or the musical composer before the performance. These three elements were left to interact by chance.

Taking the fulfillment he got from the thrill of an unpredictable performance, Arsham, with Bokaer, applied it to a more structured interaction with the design of the exhibit. While the performance was rehearsed, much of the choreography was influenced by the objects involved and the set itself. Arsham would find “things that have a potential for movement,” such as ping pong balls, so the movement of the dancers became informed by these objects, yet they were still somewhat unpredictable.

Finally, Arsham sought to take the concept of a stage and place it in the context of a gallery. “Coming from the art world, I was always used to having people walk around my sculptures. Objects that are placed on a stage have a very different relationship with the audience because you don’t walk around them.” By allowing the viewer to circulate the performance, an entirely new experience was created from an old one.

D

eveloping new ways to experience familiar scenarios has manifested itself in other areas of Arhsmam’s work as well. “Snarkitecture often tries to create the sensation that we’re not witnessing something new necessarily; we’re witnessing the transformation of something we already know,” Arsham explains, referencing the firm he co-founded with Alex Mustonen whose practice operates between art and architecture. The Snarkitecture crew sits in the front of Ashram’s studio, near a ceiling-high bookcase that covers the front wall. The productions of Snarkitecture are described by Ashram as, “objects in spaces that float somewhere between something that has a function and something that is completely useless.”

Last month, the duo designed the entrance to the Design Miami fair by creating a “cavern landscape that was based on this toy with a bunch of pins that you push your hand into.” The project, called Drift, was meant to take what people already knew about the architecture of a fair – a frame with stretched vinyl – and transform it into tubes that were wrapped and inflated. “Then we started pushing and pulling and lifting them to see what kind of space we could make.”

I asked Arsham how he and Mustonen came up with the name Snarkitecture and he explained the word references a Lewis Carroll poem called The Hunting of the Snark, in which a group of misfits are searching for a beast called the Snark. However, they don’t know what it looks like and they use a blank white map as they try to find it. Arsham relates Snarkitecture’s work to this story, concluding, “There is a search for something, but we don’t know what it is; it’s this formless entity.”

Written by Victoria Petersen

For more information, visit www.danielarsham.com